- Scripting

- Information on writing scripts to control JMRI in more detail:

- Python and Jython (General Info)

- JMRI scripts are in Jython, a version of Python, a popular general-purpose computer language

- Tools

- JMRI tools for working with your layout:

- Common Tools:

- Blocks:

- Routing and Control:

- Other:

- System-specific...

- Web server tools...

- Layout Automation

- Use JMRI to automate parts of your layout and operations:

- Supported Hardware

- JMRI supports a wide range of DCC systems, command stations and protocols.

- Applications

- By the community of JMRI.org:

JMRI: Getting Started with Scripting

The easiest way to learn how to use scripts in JMRI is to study the simplest examples first and work your way into more complex details. The sections below discuss various aspects of scripting that will help you to understand the more complex scripts found in the JMRI examples library included in the distribution and online:

- Running "Hello World"

- Basic debugging tools in JMRI

- Sample layout commands

- Access to JMRI Objects

- Script files, listeners, and classes

CAUTION: Python and its Jython variant do not use braces, brackets, or parentheses to indicate program structure, but rather rely on formatting, specifically indentation. To avoid confusion, it is STRONGLY recommended that you DO NOT USE TABS but rather use spaces (four is typical) to show statements that part of a class or controlled structure where you might have used some bracketing. Most program editors have a setting to automatically changes tabs to a set number of spaces to make this easier.

Running "Hello World"

To do that:

-

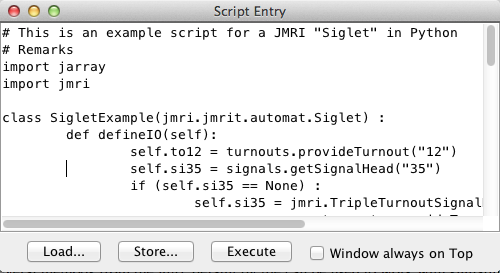

From the

Scripting {Old: Panels} menu, select

Script Entry. This will give you a window where you can type one or

more commands to execute. (Note that it might take a little while the first time you do

this as the program finds its libraries; it will be faster the next time) The commands

stay in the window, so you can edit them and rerun them until you like them.

From the

Scripting {Old: Panels} menu, select

Script Entry. This will give you a window where you can type one or

more commands to execute. (Note that it might take a little while the first time you do

this as the program finds its libraries; it will be faster the next time) The commands

stay in the window, so you can edit them and rerun them until you like them.

- From the Scripting {Old: Panels} menu, select Script Output. This creates a window that shows the output from the script commands you issue.

- To see this in operation, type

print "Hello World"in the input window, and click "Execute". You should see the output in the Script Output window immediately:>>> print "Hello World" Hello World - Python also evaluates expressions, etc. Remove the contents of the input window

(select it and hit delete), and enter

print 1+2then click execute. The output window should then show something like:>>> print 1+2 3

Basic debugging tools in JMRI

JMRI does not provide a full "development environment," but it does provide some basic information that can help with debugging your scripts.

Open the JMRI System Console window (Help ⇒ System Console). This will give you instant information pertaining to WARN and ERROR messages. Text can be copied to a text editor for further review.

Open the Script Output window (Scripting {Old: Panels} ⇒ Script Output). This will display the results of any "print" statements in your script as well as some error messages (NOTE that some errors go here and some to the System Console so you you should have both windows open when you are debugging). Text can be copied to a text editor for further review.

Investigate the information found in the technical reference to be better able to insert more of your own DEBUG and INFO messages into the session.log file, and also the JMRI System Console window. You might also investigate the "default_lcf.xml" file that is described in that link.

Note to Mac OS users: BBEdit and similar tools do some syntax checking. For PC users, Notepad++ is a good tool for getting indentation correct.

Sample layout commands

>>> lt1 = turnouts.provideTurnout("1")

>>> lt1.setCommandedState(CLOSED)

>>> print lt1.commandedState

2

>>> lt1.commandedState = THROWN

>>> print lt1.commandedState

4

>>> turnouts.provideTurnout("1").getCommandedState()

1

Note that this is running a complete version of the JMRI application; all of the windows and menus are presented the same way, configuration is done by the preferences panel, etc. What the Jython connection adds is a command line from which you can directly manipulate things.

This also shows some of the simplifications that Jython and the Python language brings to using JMRI code. The Java member function:

turnout.SetCommandedState(jmri.Turnout.CLOSED);

can also be expressed in Jython as:

turnout.commandedState = CLOSED

This results in much easier-to-read code.

There are a lot of useful Python books and online tutorials. For more information on the Jython language and it's relations with Java, the best reference is the Jython Essentials book published by O'Reilly. The jython.org web site is also very useful.

Access to JMRI Objects

Turnout t2 = InstanceManager.getDefault(TurnoutManager.class).newTurnout("LT2", "turnout 2");

t2.SetCommandedState(Turnout.THROWN)

Jython simplifies that by allowing us to provide useful variables, and by shortening certain

method calls.

To get easier access to the SignalHead, Sensor and Turnout managers and the CommandStation object, several shortcut variables are defined:

- sensors

- turnouts

- lights

- signals (SignalHeads)

- masts (SignalMasts)

- routes

- blocks

- reporters

- idtags

- memories

- powermanager

- addressedProgrammers

- globalProgrammers

- dcc (current command station)

- audio

- shutdown (current shutdown manager)

- layoutblocks

- warrants

- sections

- transits

t2 = turnouts.provideTurnout("12");

Note that the variable t2 did not need to be declared.

Jython provides a shortcut for parameters that have been defined with Java-Bean-like get and set methods:

t2.SetCommandedState(Turnout.THROWN)

can be written as

t2.commandedState = THROWN

where the assignment is actually invoking the set method.

Also note that THROWN was defined when running the Python script at startup;

CLOSED, ACTIVE, INACTIVE, ON, OFF, INCONSISTENT,

LOCKED, UNLOCKED, PUSHBUTTONLOCKOUT, CABLOCKOUT,

RED, YELLOW, GREEN, LUNAR, DARK,

FLASHRED, FLASHYELLOW, FLASHGREEN are also defined. (

These shortcut bindings are defined in Java )

A similar mechanism can be used to check the state of something:

>>> print sensors.provideSensor("3").knownState == ACTIVE

1

>>> print sensors.provideSensor("3").knownState == INACTIVE

0

Note that Jython uses "1" to indicate true, and "0" to indicate false, so sensor 3 is

currently active in this example. You can also use the symbols "True" and "False" respectively.

You can directly invoke more complicated methods, e.g. to send a DCC packet to the rails you type:

dcc.sendPacket([0x01, 0x03, 0xbb], 4)

This sends that three-byte packet four times, and then returns to the command line. Also see

JMRI Jython : The difference between System Names and User

Names

Script files, listeners, and classes

[See also the scripting "How To" page for more information on these topics.]

Scripting would not be very interesting if you had to type the commands each time. So you can put scripts in a text file and execute them by selecting the "Run Script..." menu item, or by using the "Advanced Preferences" to run the script file when the program starts.

Although the statements we showed above were so fast you couldn't see it, the rest of the program was waiting while you run these samples. This is not a problem for a couple statements, or for a script file that just does a bunch of things (perhaps setting a couple turnouts, etc) and quits. But you might want things to happen over a longer period, or perhaps even wait until something happens on the layout before some part of your script runs. For example, you might want to reverse a locomotive when some sensor indicates it's reached the end of the track.

There are a couple of ways to do this. First, your script could define a "listener", and attach it to a particular sensor, turnout, etc. A listener is a small subroutine which gets called when whatever it's attached to has it's state change. For example, a listener subroutine attached to a particular turnout gets called when the turnout goes from thrown to closed, or from closed to thrown. The subroutine can then look around, decide what to do, and execute the necessary commands. When the subroutine returns, the rest of the program then continues until the listened-to object has it's state change again, when the process repeats.

For more complicated things, where you really want your script code to be free-running within the program, you define a "class" that does what you want. In short form, this gives you a way to have independent code to run inside the program. But don't worry about this until you've got some more experience with scripting.